Background

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan was damaged in the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Japan used water to cool the reactors, causing the water to become contaminated. After 12 years, Japan began releasing wastewater into the sea on August 24, 2023, as part of a continuous process that will take at least 30 years.

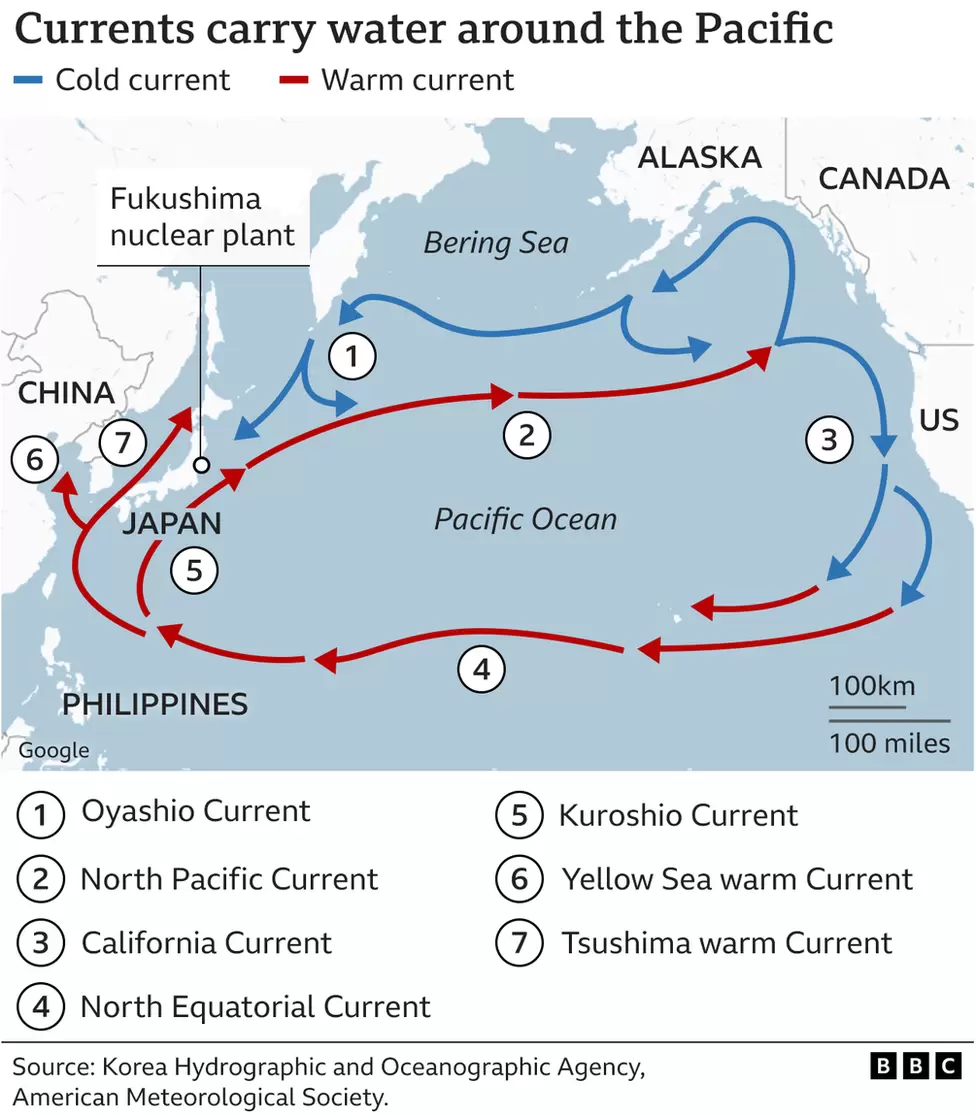

Currents carry water around the Pacific.

Currents carry water around the Pacific.

Is the released water safe? According to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA):

"Based on its comprehensive assessment, the IAEA has concluded that the approach to the discharge of ALPS treated water into the sea, and the associated activities by TEPCO, NRA, and the Government of Japan, are consistent with relevant international safety standards."

However, the release of wastewater has been met with varied responses across different countries, where social media plays a critical role in amplifying these voices, shaping public sentiment through information, or potentially misleading them through coordinated campaigns.

In this report, we investigate and demostrate the presence of coordinated campaigns and science misinformation related to Fukushima waste water release on social media.

All data and analysis are collected and generated by Information Tracer, our proprietary software.

Step 1: Identify main narratives

What we search: After manually reviewing posts, we used the following queries to capture discussions related to Fukushima waste water release:

- "fukushima AND negligible" (implying the health impact is minimal)

- "(fukushima_is_safe) OR (fukushima AND safe)"

- "fukushima AND science"

- "fukushima AND health"

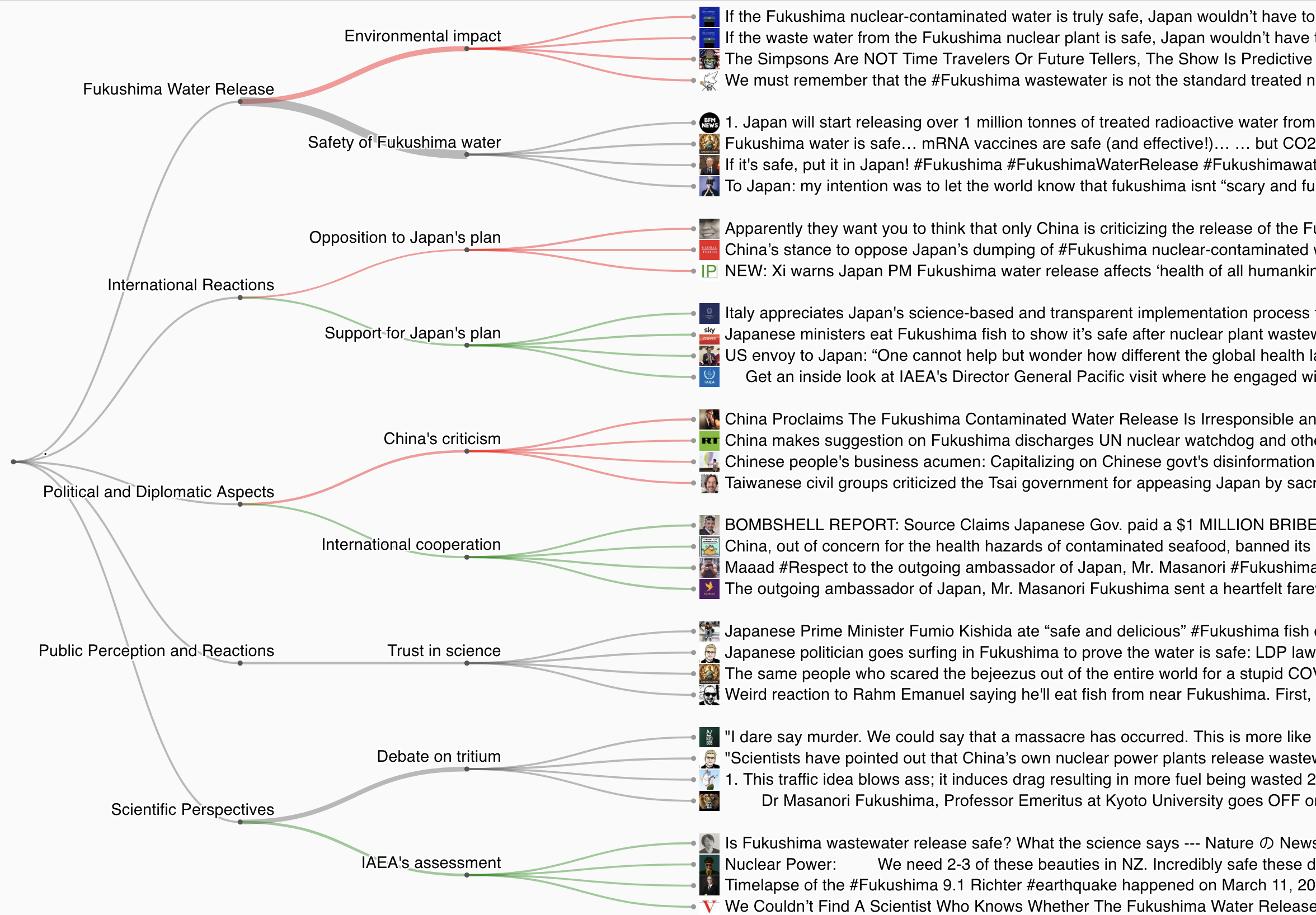

Narratives related to Fukushima waste water release on social media. Positive negatives are colored green, and negative colored red.

Narratives related to Fukushima waste water release on social media. Positive negatives are colored green, and negative colored red.

What we find: International organizations, diplomats, and social influencers all contribute to the discussion. There are various narratives, such as concerns about the environmental impact, debate on the trust in science, etc,.

Above all, the key discussion point is "is the water safe?", for which there are two competing narratives:

- 1. "nuclear wastewater is safe". People who support this narrative are associated with pro-Japan western countries.

- 2. "nuclear wastewater is not safe". People who support this narrative are associated with China.

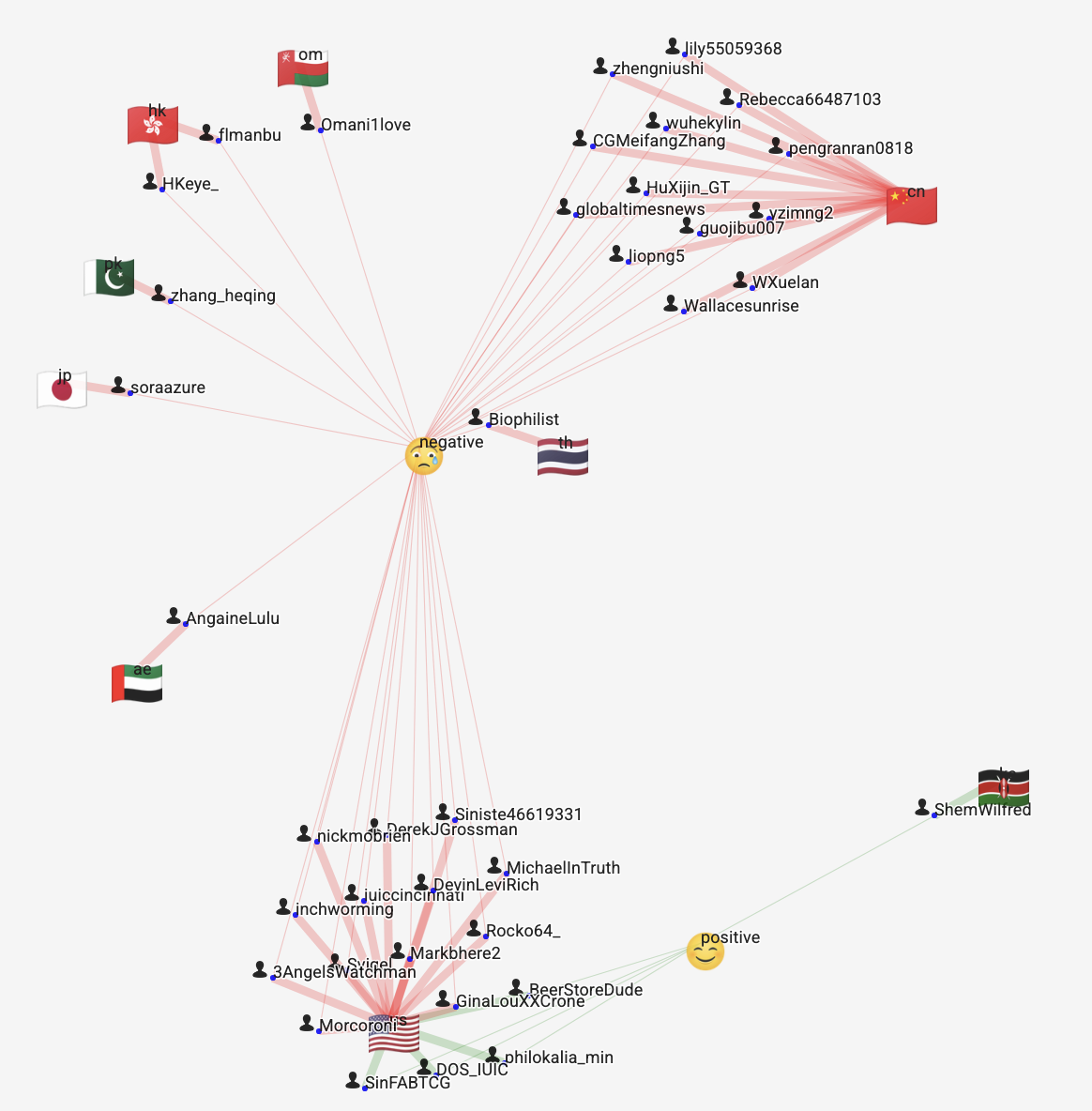

The focus -- water safety -- is a scientific issue, but the narrative divide aligns well with geo-political alliances. The image below shows Twitter user sentiment and their country of origin.

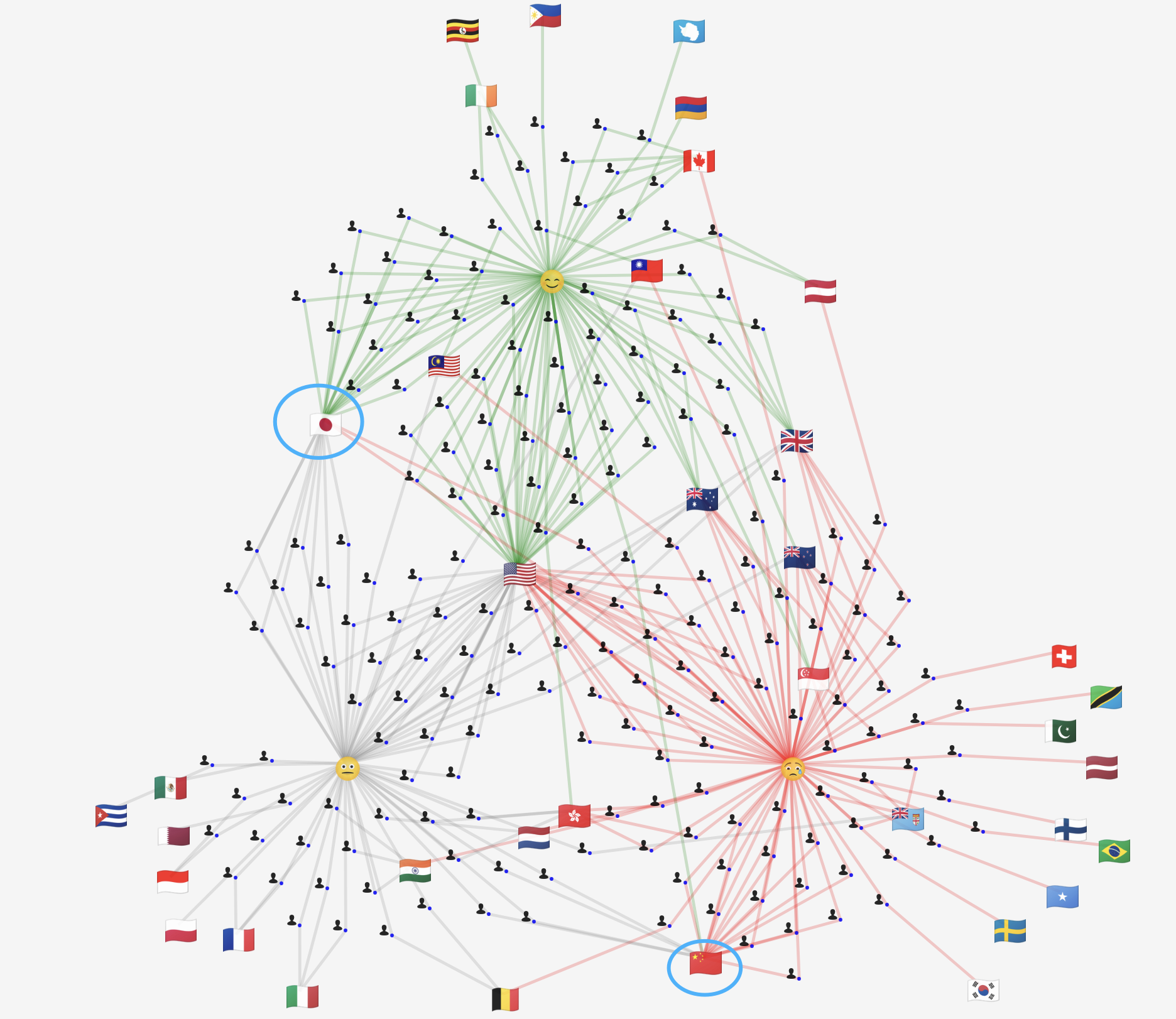

Social media users, their country of origin, and their sentiments towards Fukushima waste water. China has a strong negative opinion, while Japan has a strong positive view.

Social media users, their country of origin, and their sentiments towards Fukushima waste water. China has a strong negative opinion, while Japan has a strong positive view.

In the table below, we list major influencers behind each narrative. The basis of their arguments can be summarized as:

- "water is safe" group rely on IAEA reports and scientific research.

- "water is not safe" group largely lack scientific evidence and instead use rhetorical arguments such as "if it’s safe, put in japan"

Account Information

| Account Name | Evidence | Link | Attitude |

|---|---|---|---|

Ambassador of Canada to Japan Ambassador of Canada to Japan

|

IAEA | View | Support |

Italy in Japan Italy in Japan |

IAEA | View | Support |

US envoy to Japan US envoy to Japan |

due diligence, openness and international cooperation | View | Support |

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan |

Science report | View | Support |

IAEA Director General of the @IAEAorg

IAEA Director General of the @IAEAorg |

IAEA | View | Support |

Zhang Heqing, cultural counselor at the embassy of the People's Republic of China (PRC) to Pakistan

Zhang Heqing, cultural counselor at the embassy of the People's Republic of China (PRC) to Pakistan |

“If it’s safe, put in Japan” | View | Against |

Embassy of the People's Republic of China in Fiji

Embassy of the People's Republic of China in Fiji |

“If it’s safe, put in japan” | View | Against |

Consul General of China in Belfast UK Consul General of China in Belfast UK |

“If it’s safe, put in japan” | View | Against |

By closely examining the table above, we observed many Chinese accounts repeatedly post the same phrase, “If it’s safe, put it in Japan.” This raises the question: is this evidence of a coordinated campaign?

A coordinated campaign on social media is a deliberate and organized effort by individuals, groups, or entities to spread specific messages, narratives, or agendas across social media platforms.

“If it’s safe put in Japan”

What we search: “If it’s safe put in Japan”

What we find:

Initial spread on Facebook

The slogan was first posted by the Fiji Exposed Forum on Facebook, a local news channel, but it did not initially gain significant attention. However, when the Chinese state-affiliated media account "Trending in China" mentioned this protest, the engagement spiked, tripling its audience reach within a single day.

Facebook Surge

Following this surge, major Chinese media outlets, including People’s Daily and CGTN Frontline, joined in spreading the message, further amplifying its visibility on Facebook.

Twitter Surge

On Aug 28th, Chinese Counsellor Zhang Heqing tweeted the same phrase, with a video about a protest in Fiji from ChinaDaily.

On Aug 29th, another Chinese Counsellor Zhang Meifang posted a similar tweet.

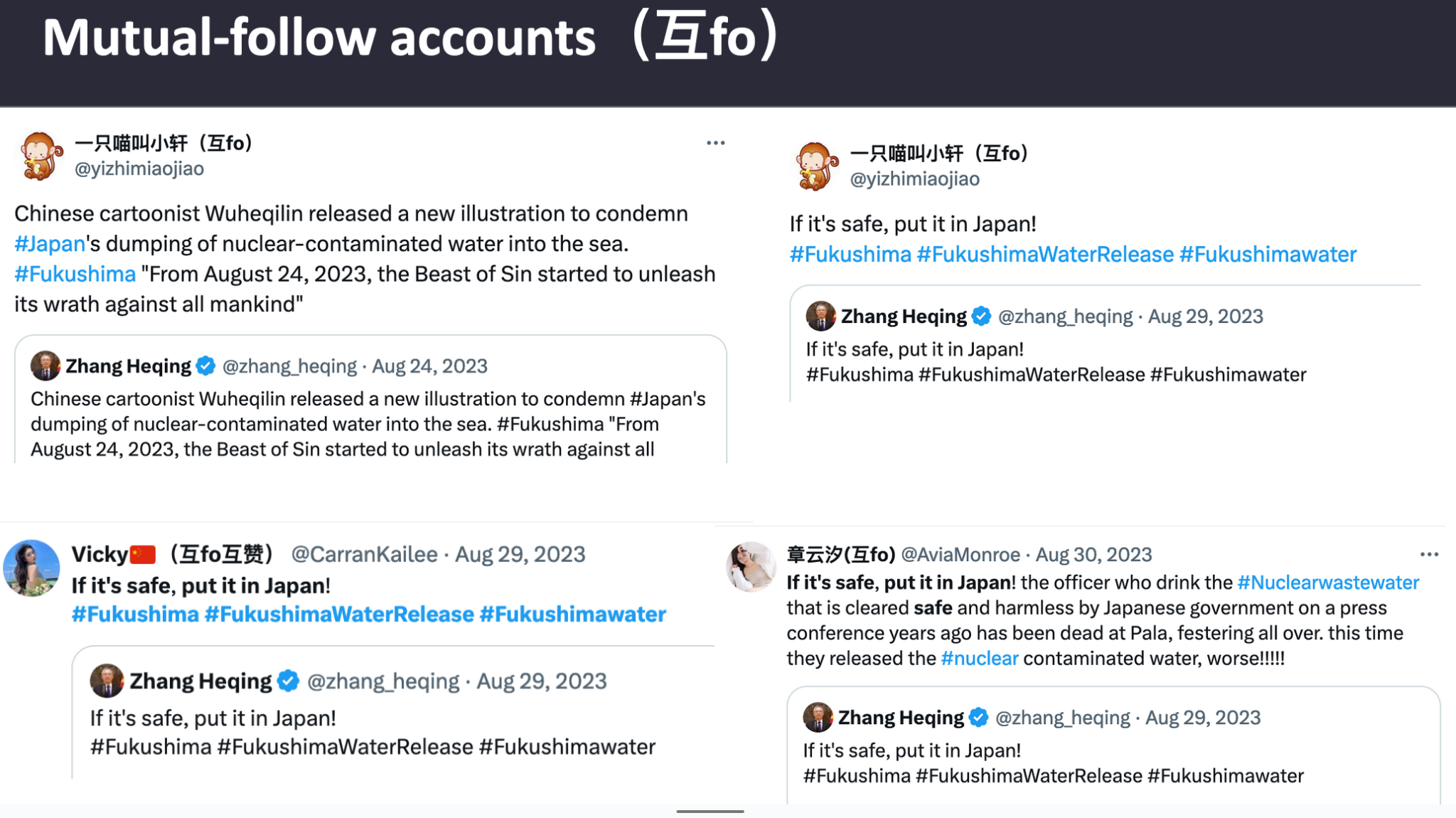

The same narrative is shared by pro-China accounts following each other, with similar account names and bio.

"Follow each other" accounts posting the same phrase "If it's safe put in Japan".

"Follow each other" accounts posting the same phrase "If it's safe put in Japan".

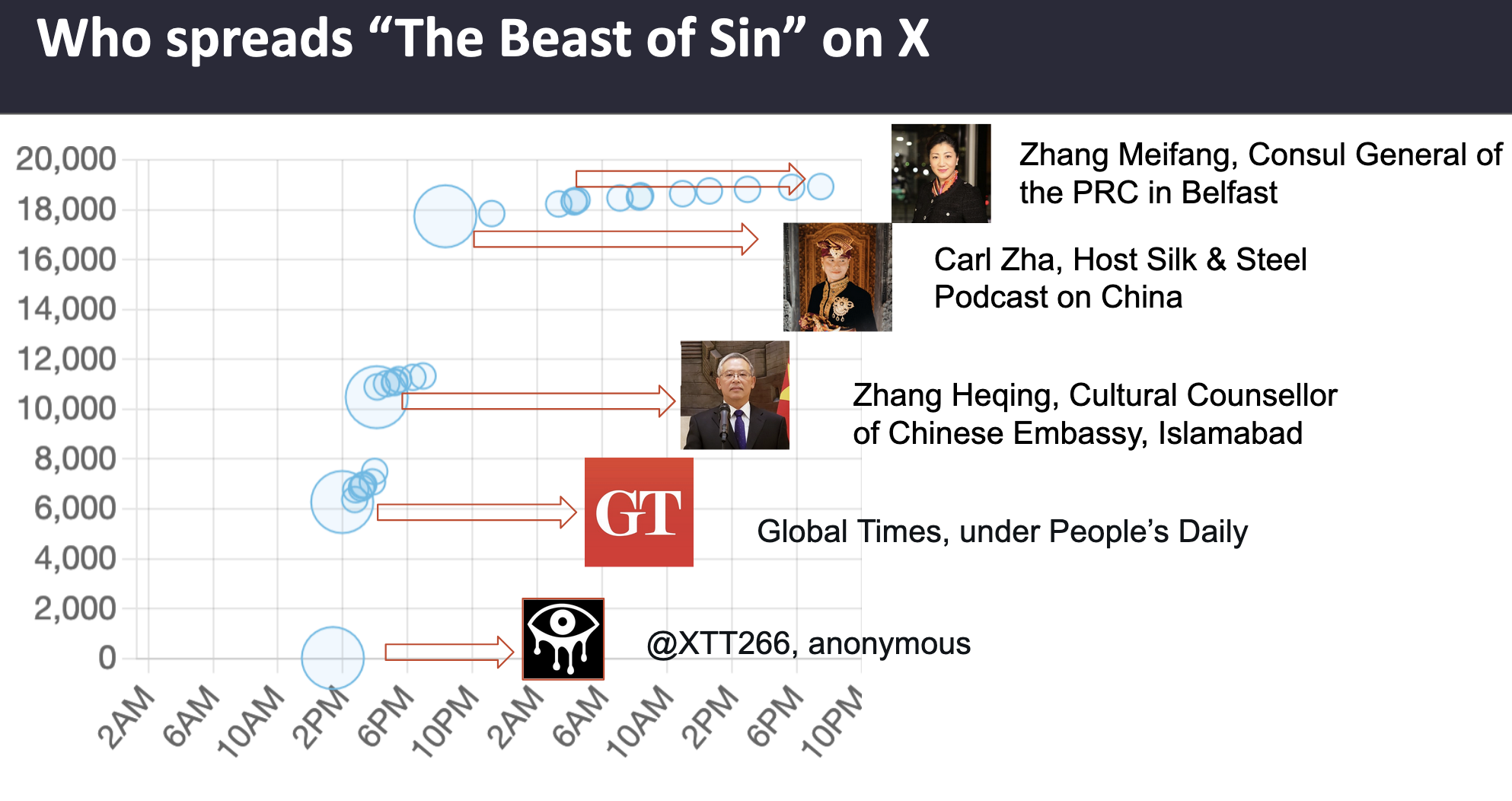

“The Beast of Sin”

"The Beast of Sin" drawing.

"The Beast of Sin" drawing.

During our investigation, an image called “The Beast of Sin” stood out. The image was created by Wuheqilin (乌合麒麟), a Chinese cartoonist known for his nationalist and provocative artwork.

Often referred to as the “Wolf Warrior Artist,” he has gained a reputation for producing politically charged illustrations that align with nationalist narratives.

What we search:“The Beast of Sin”

What we find:

On August 24, this image was shared on Twitter by Chinese diplomats, Chinese media and other accounts.

Spread of "The Beast of Sin" narrative on X.

Spread of "The Beast of Sin" narrative on X.

The image stirred up strong emotions regarding the nuclear wastewater release. To quantify the impact, we weighted the sentiment based on the number of interactions each post received. The analysis revealed that countries such as China and Pakistan exhibited particularly strong opposing sentiments toward Fukushima.

X users that post 'the beast of sin'. The sentiment towards Fukushima water release is mostly negative, from countries such as China.

X users that post 'the beast of sin'. The sentiment towards Fukushima water release is mostly negative, from countries such as China.

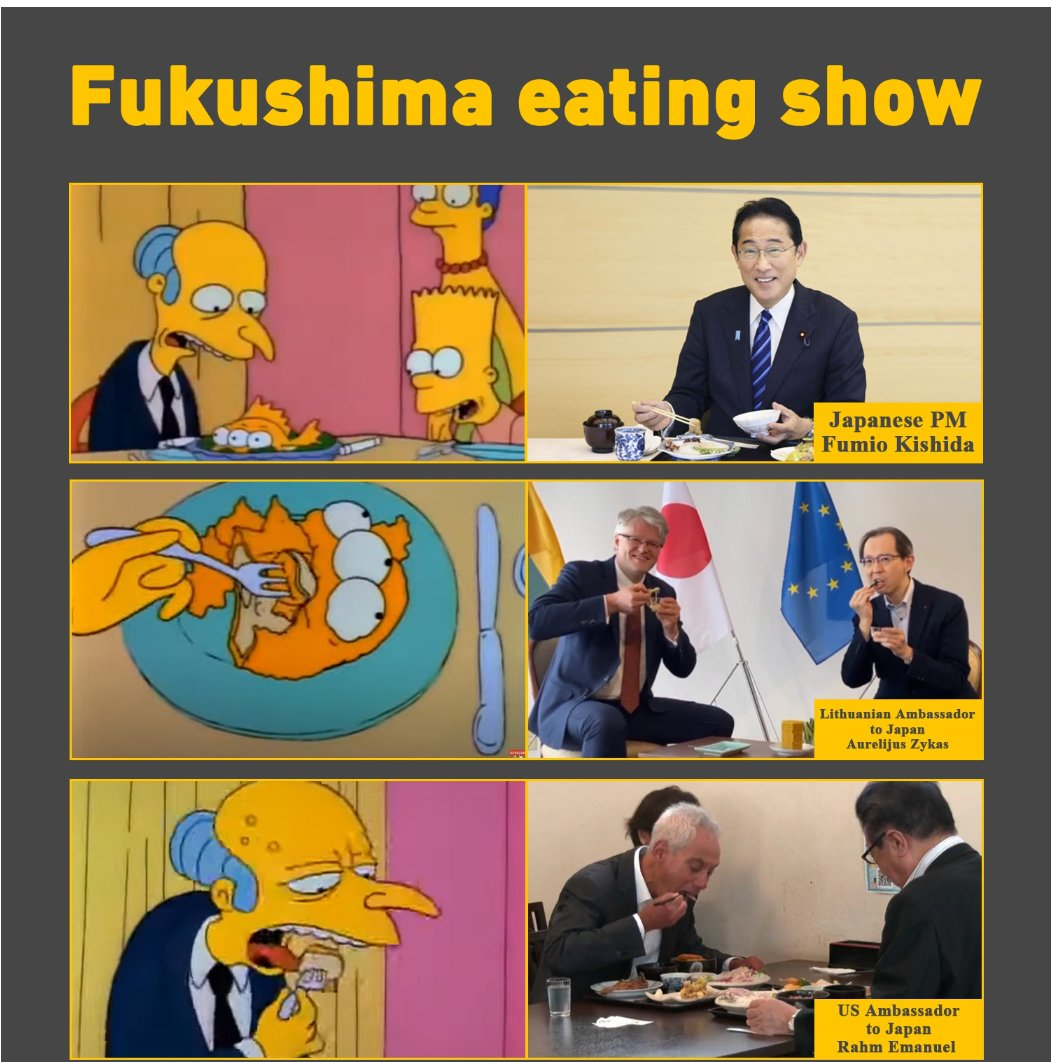

“Simpsons Fukushima”

On August 30, 2023, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida publicly ate fish from Fukushima to dispel concerns after the nuclear wastewater release. Other figures, such as the Australian Ambassador to Japan, also joined him to demonstrate support.

Soon after, memes comparing The Simpsons with Japanese Prime Minister began circulating on the Internet. The meme seems to suggest that officials consumed seemingly contaminated food to prove its safety.

We are curious, is this coordinated?

Meme about Simpsons and Fukushima.

Meme about Simpsons and Fukushima.

What we search: "Simpsons Fukushima".

What we find: There are several key influencers amplifying the meme, including Hu Xijin, a Chinese journalist and former chief editor of Global Times; New York Post and Insider Paper, both New York-based media outlets; and Wall Street Apes, a popular account associated with the r/WallStreetBets subreddit.

While Chinese accounts were actively involved in spreading the meme, the engagement was not limited to a single nationality or region. Influencers and media from different countries contributed to its virality simultaneously, indicating that the spread was organic rather than coordinated.

Conclusion

We hope this report makes you think: when the amount of information we receives exceeds our ability to process, what should we do? Who should we trust? There is no simple answer. Taking a bit of time to search and verify what we see on the Internet, would be a good first step.Acknowledgement: We are grateful for the Pulitzer Center who provided funding for this investigation. We want to thank Professor Haohan Chen from The University of Hong Kong and Katrine Krogh Pedersen from The University of Copenhagen for developing workshops with us. We also want to thank digital media outlets and their editors who help publish our works.